I recently watched The Glad Philanderer again, that penetrating 1959 film by Witold Khanken about the life of the Hungarian dramatist Tolbin Roth. When I first saw it in college I was puzzled by its grainy, poorly focused cinematography, mistaking this well-reasoned aesthetic choice for the rank incompetence of an amateur. Arguing through the night with my roommates, I reached the conclusion that Modern Art was a hoax - a snide, treacherous folly imposed upon us by a privileged class of well-connected powerful snobs.

Now, of course, I can fully appreciate Khanken's masterpiece for what it is but recalling my initial reaction to the film I am struck, once again by the tremendous personal risks great artists assume while communicating in a prophetic diction.

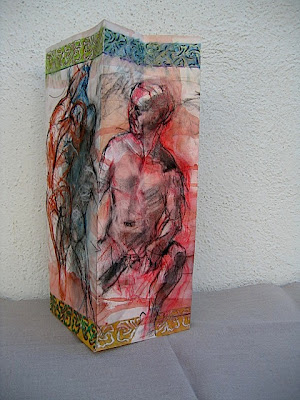

|

| Still from The Glad Philanderer, Witold Khanken 1959 |

Like Khanken and his subject Tolbin Roth, my uncle Micah Carpentier was naturally and inevitably drawn to the visionary tropes of the solitary genius. He, like they, were scorned at first. Not only were they mocked and misunderstood but were regarded as downright fraudulent by a public too lazy and opaque to be receptive to revelation. And just as Roth went on to become a household name so too did Carpentier yet both paid a steep price for their success.

The actor Marel Szolnoky who played Roth in Khanken's epic film was revered in his native Hungary. People of a certain age still

speak solemnly of his portrayal of Lear in Szabó's stage adaptation of the Shakespeare classic. And like my uncle, Szolnoky came to the United States to widen his audience and to chase the American Dream. When Szolnoky came to Hollywood in the late 1960s his frustrated attempts to break into the business led him to the brink of despair. Aside from the few small roles given to him out of pity by Roman Polanski, he ended up working for a tailor in downtown Los Angeles.

When Carpentier came to the States he wisely chose New York to stake his claim. He quickly fell in with a group of artists and writers that included the likes of Leland Bell, Ad Reinhardt, Kenneth Koch and Kenny Pauta. He regularly showed his work at the Green Gallery on 57th Street and received, for the most part, favorable reviews. Drawn to the ideals of the Cuban Revolution, Carpentier returned to Havana in 1968 on the same Air France flight as Eldridge Cleaver.

It is so easy in life to make the wrong decision. Some blame fate but I believe the truth is much colder than that. I have devoted myself to curating the legacy of my brilliant uncle because I feel duty-bound to rectify his failure of agency, his folly and his short-sighted infatuation with a corrupted ideology.

I also need to figure out what to do with all of these bags.

|

| Marel Szolnoky |

speak solemnly of his portrayal of Lear in Szabó's stage adaptation of the Shakespeare classic. And like my uncle, Szolnoky came to the United States to widen his audience and to chase the American Dream. When Szolnoky came to Hollywood in the late 1960s his frustrated attempts to break into the business led him to the brink of despair. Aside from the few small roles given to him out of pity by Roman Polanski, he ended up working for a tailor in downtown Los Angeles.

When Carpentier came to the States he wisely chose New York to stake his claim. He quickly fell in with a group of artists and writers that included the likes of Leland Bell, Ad Reinhardt, Kenneth Koch and Kenny Pauta. He regularly showed his work at the Green Gallery on 57th Street and received, for the most part, favorable reviews. Drawn to the ideals of the Cuban Revolution, Carpentier returned to Havana in 1968 on the same Air France flight as Eldridge Cleaver.

It is so easy in life to make the wrong decision. Some blame fate but I believe the truth is much colder than that. I have devoted myself to curating the legacy of my brilliant uncle because I feel duty-bound to rectify his failure of agency, his folly and his short-sighted infatuation with a corrupted ideology.

I also need to figure out what to do with all of these bags.